LIBRARY

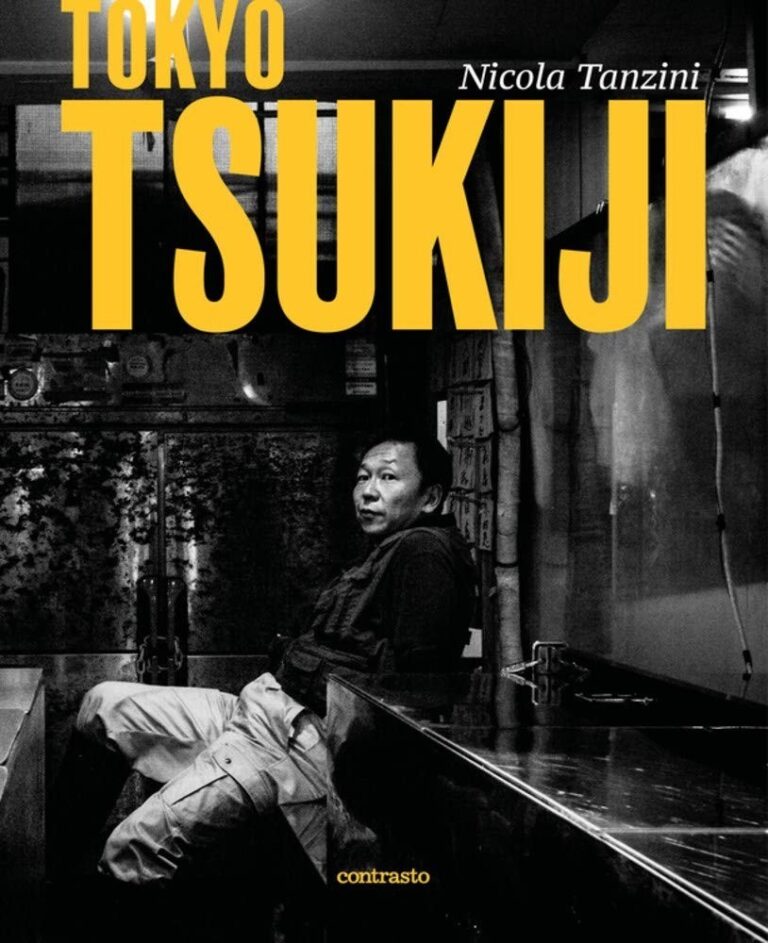

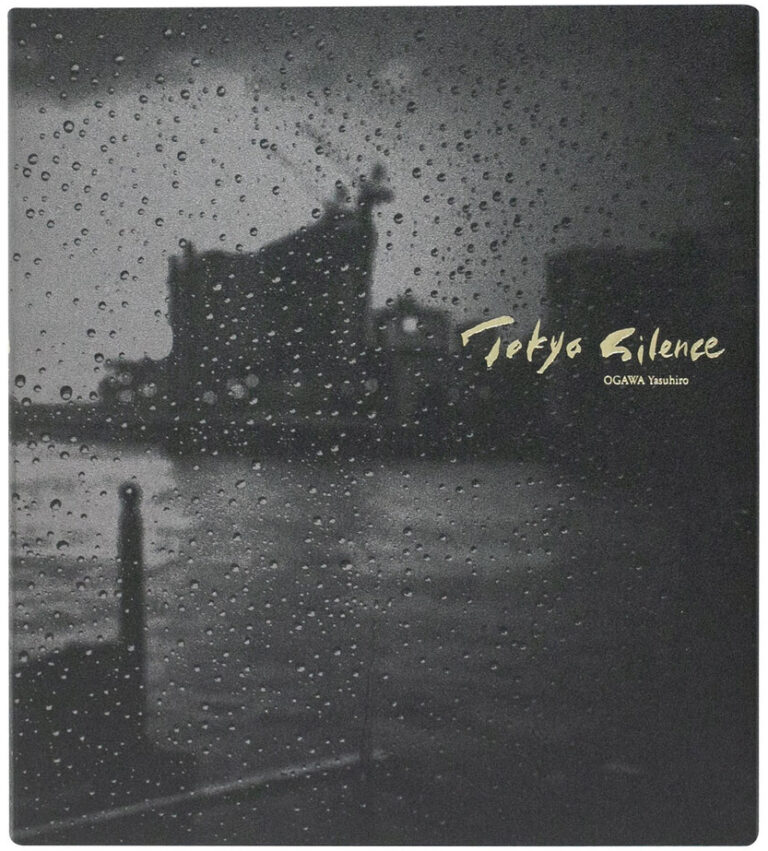

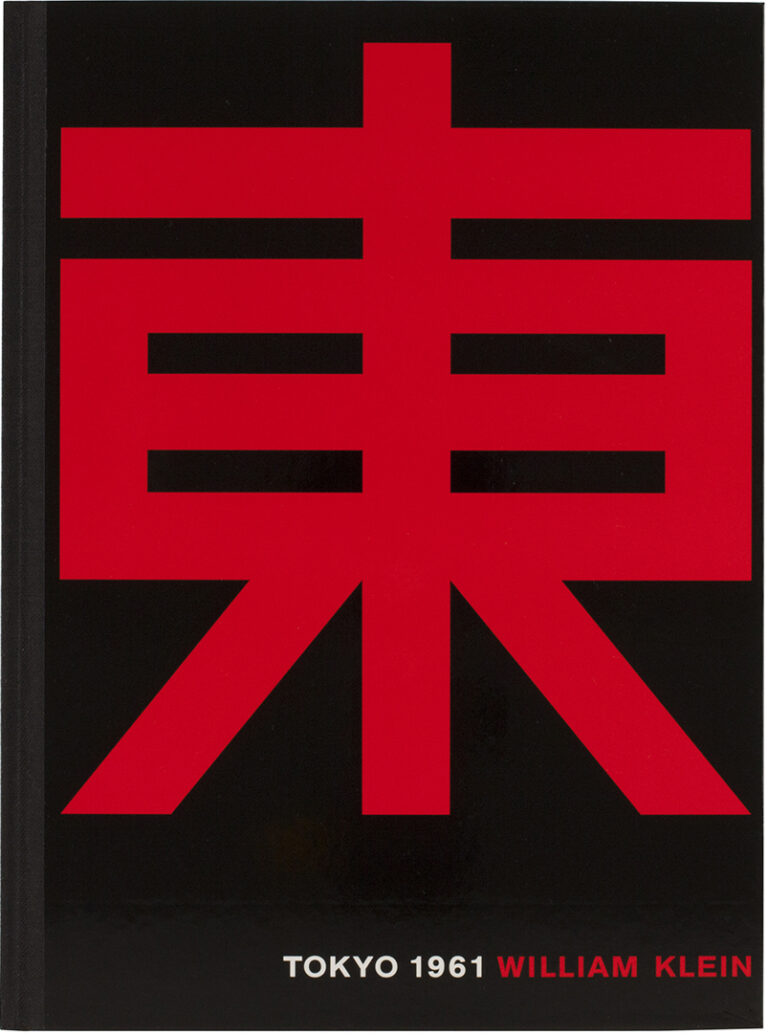

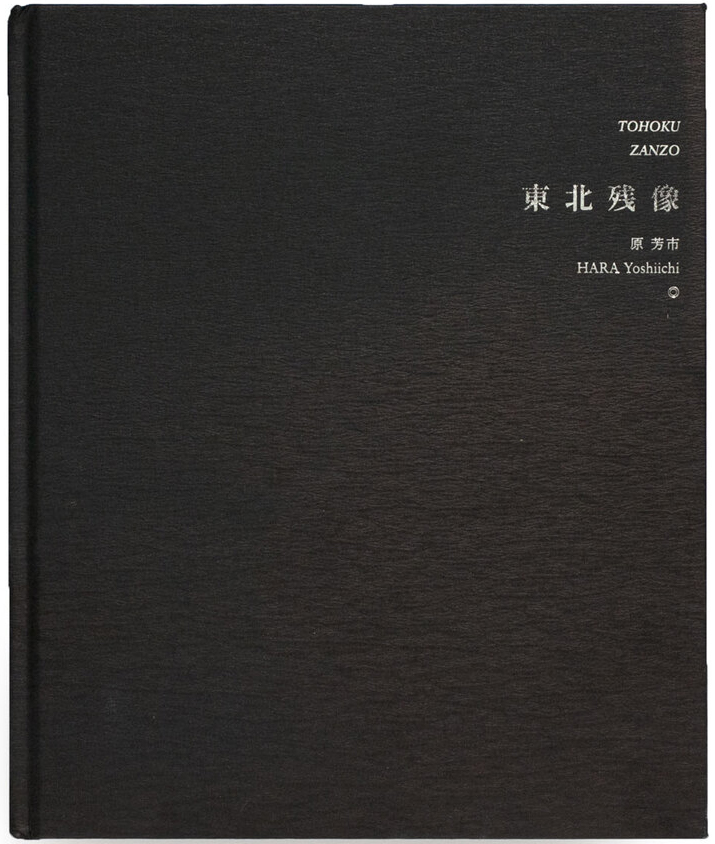

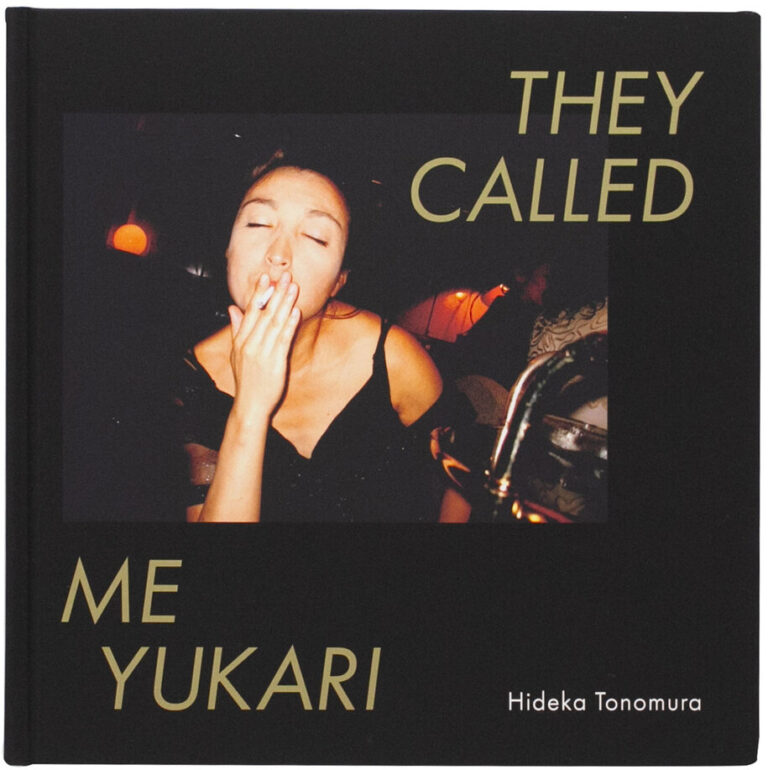

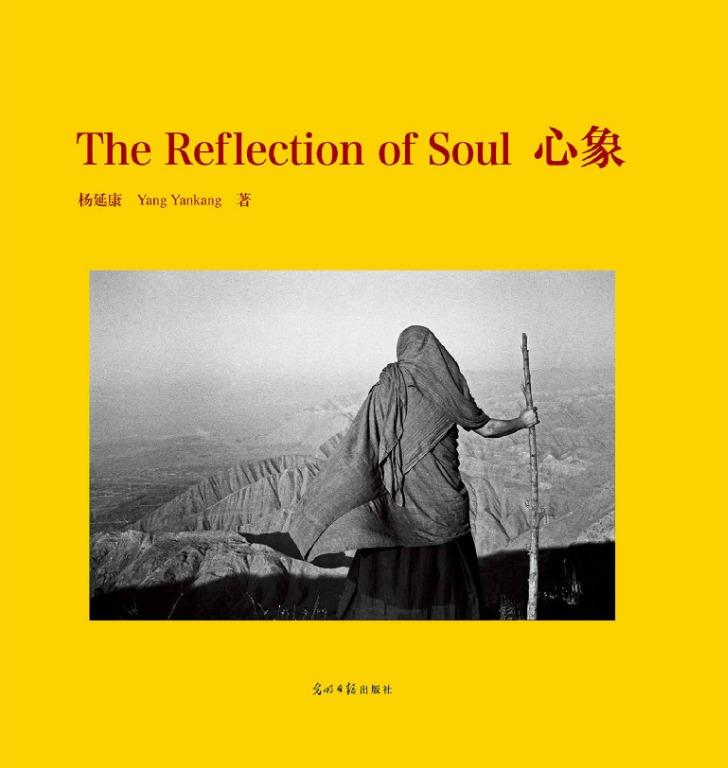

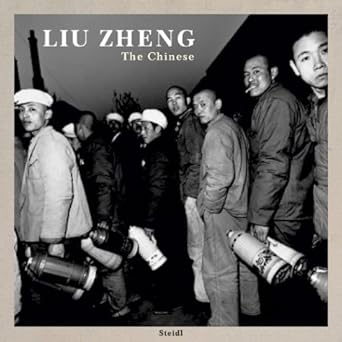

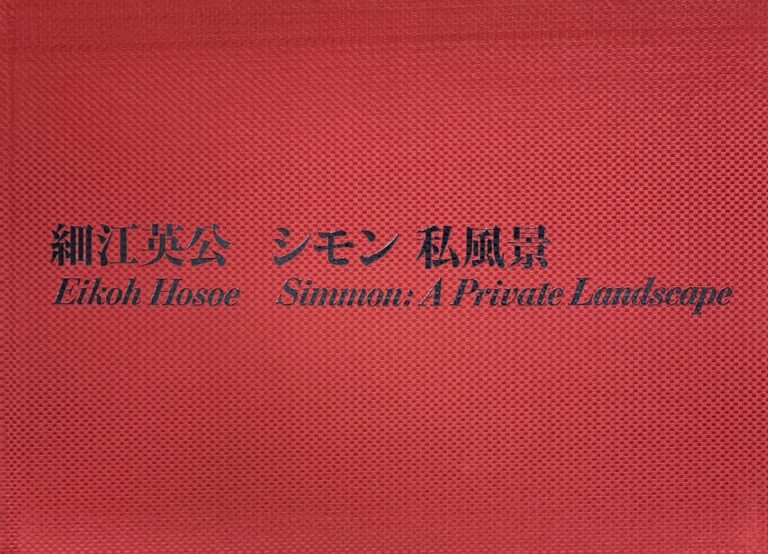

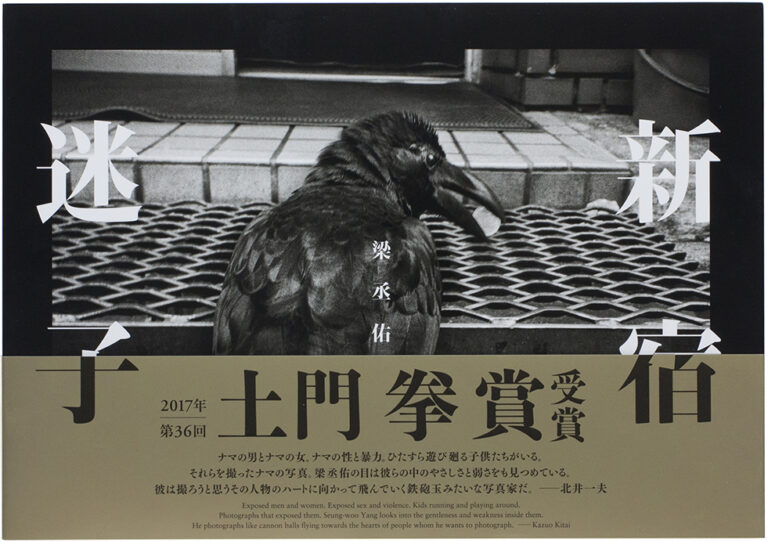

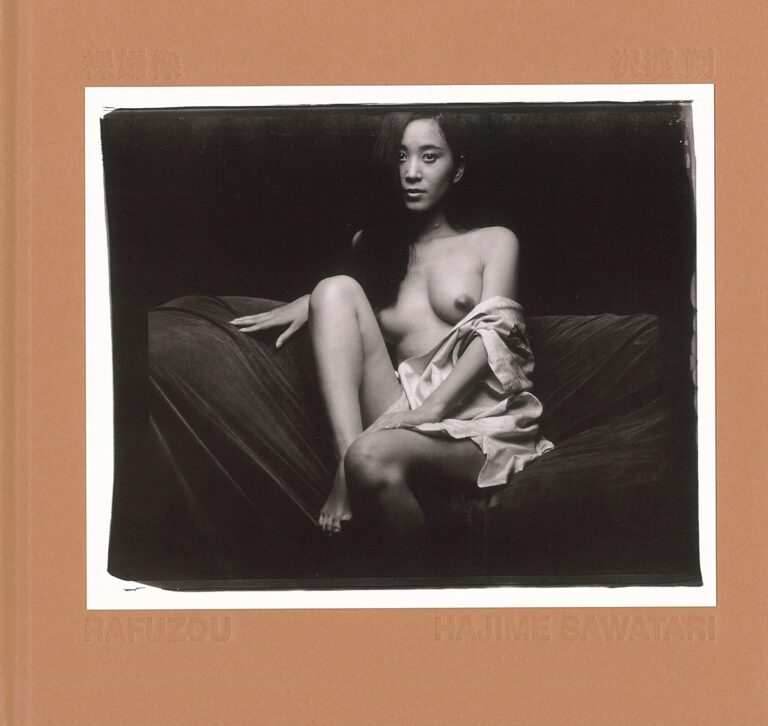

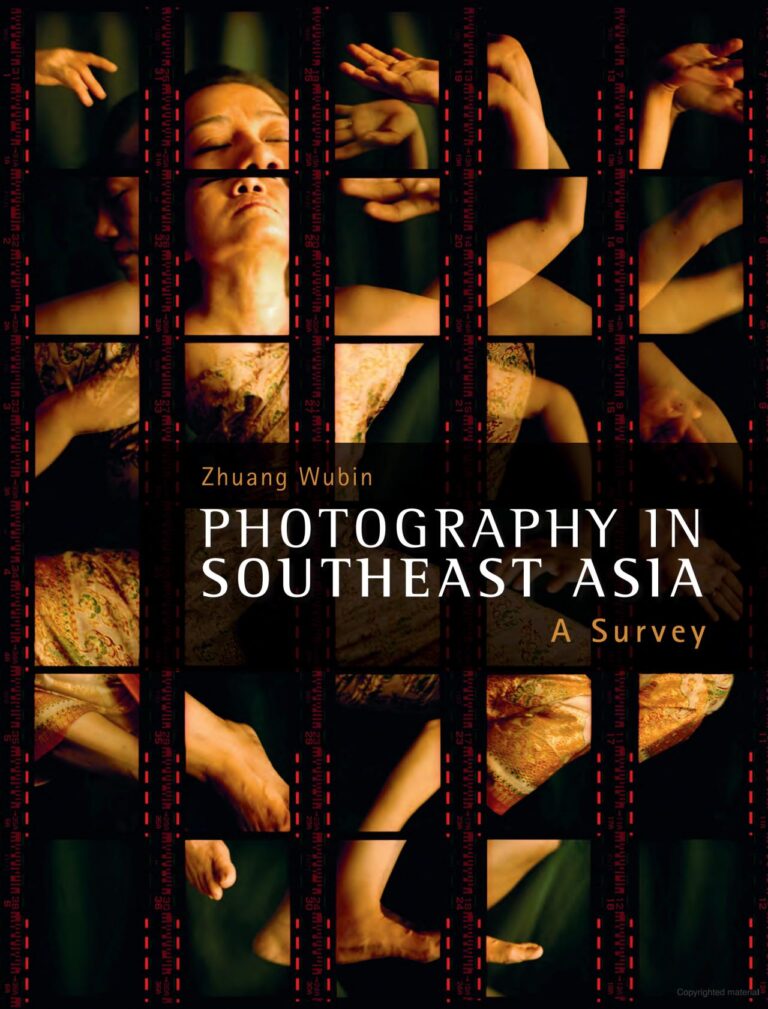

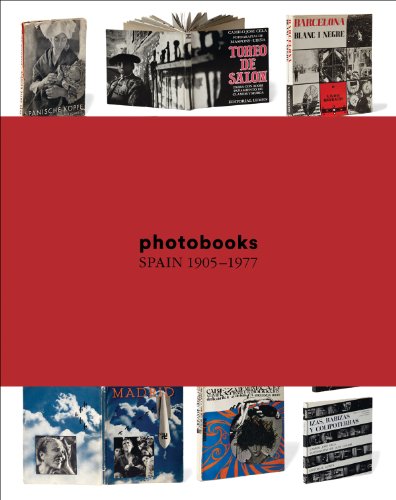

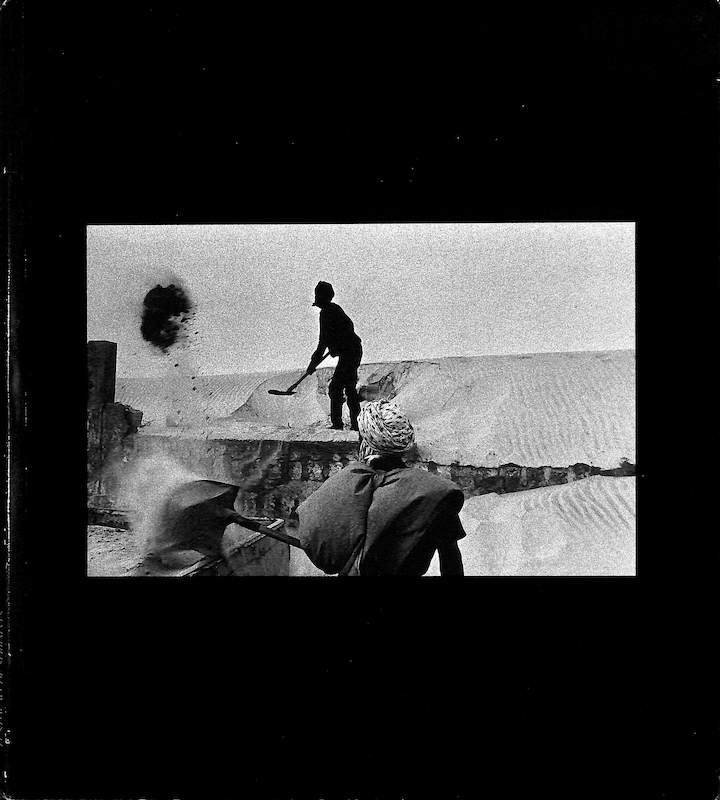

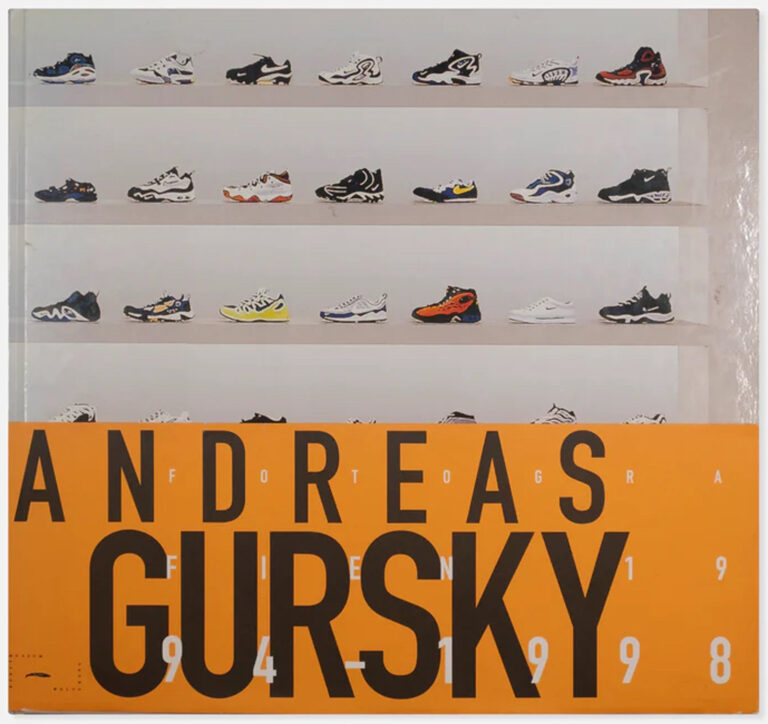

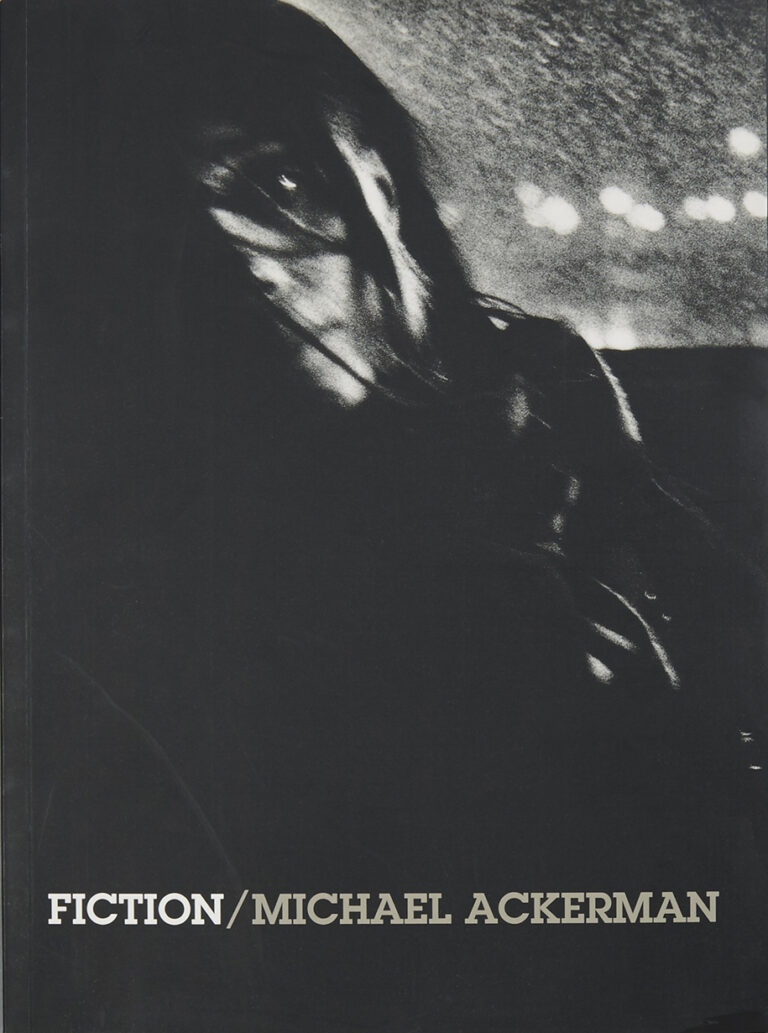

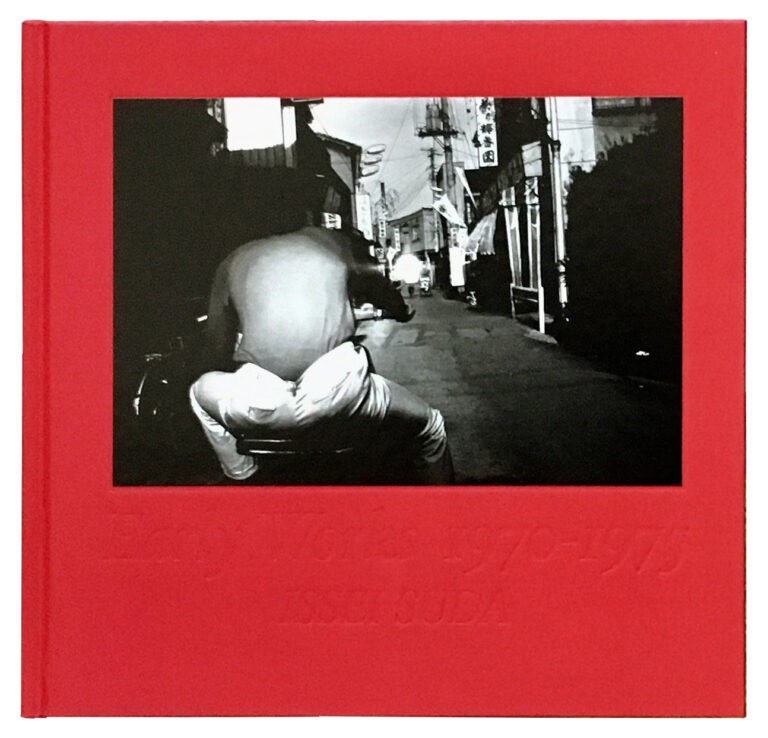

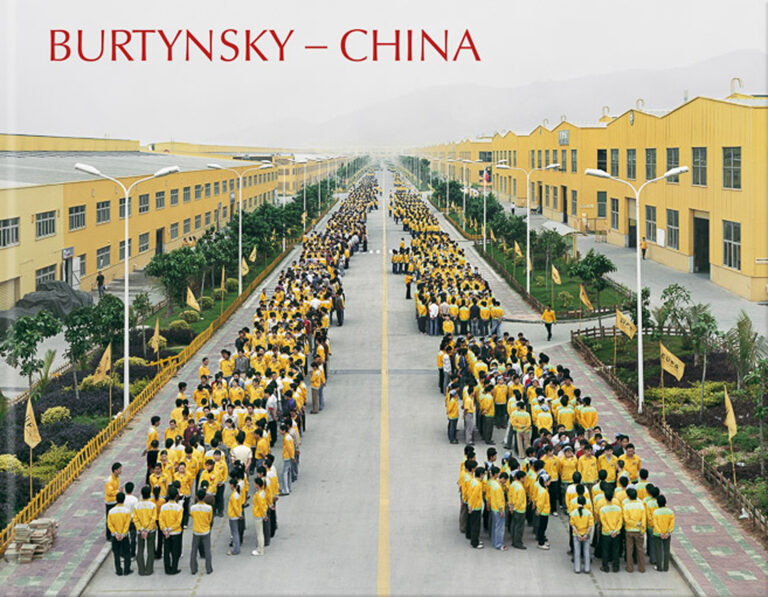

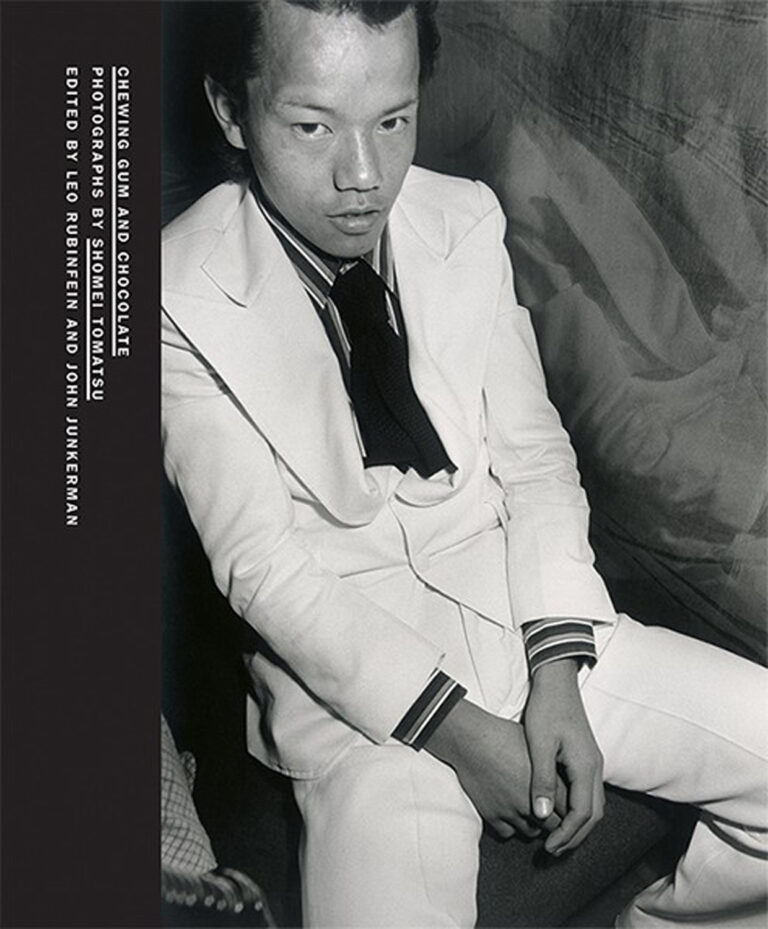

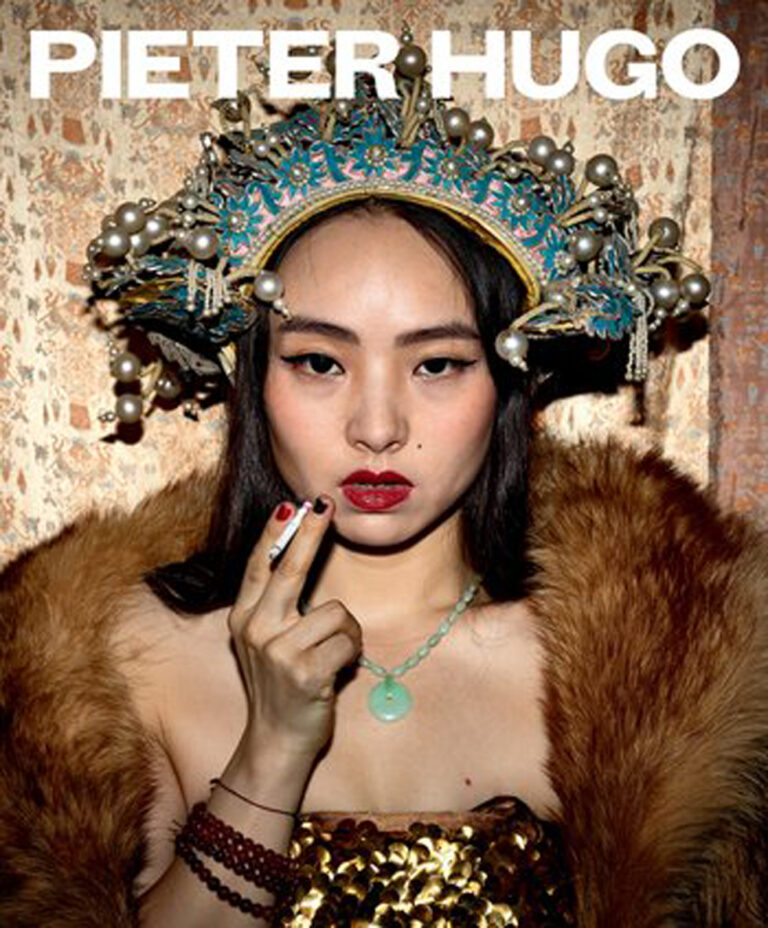

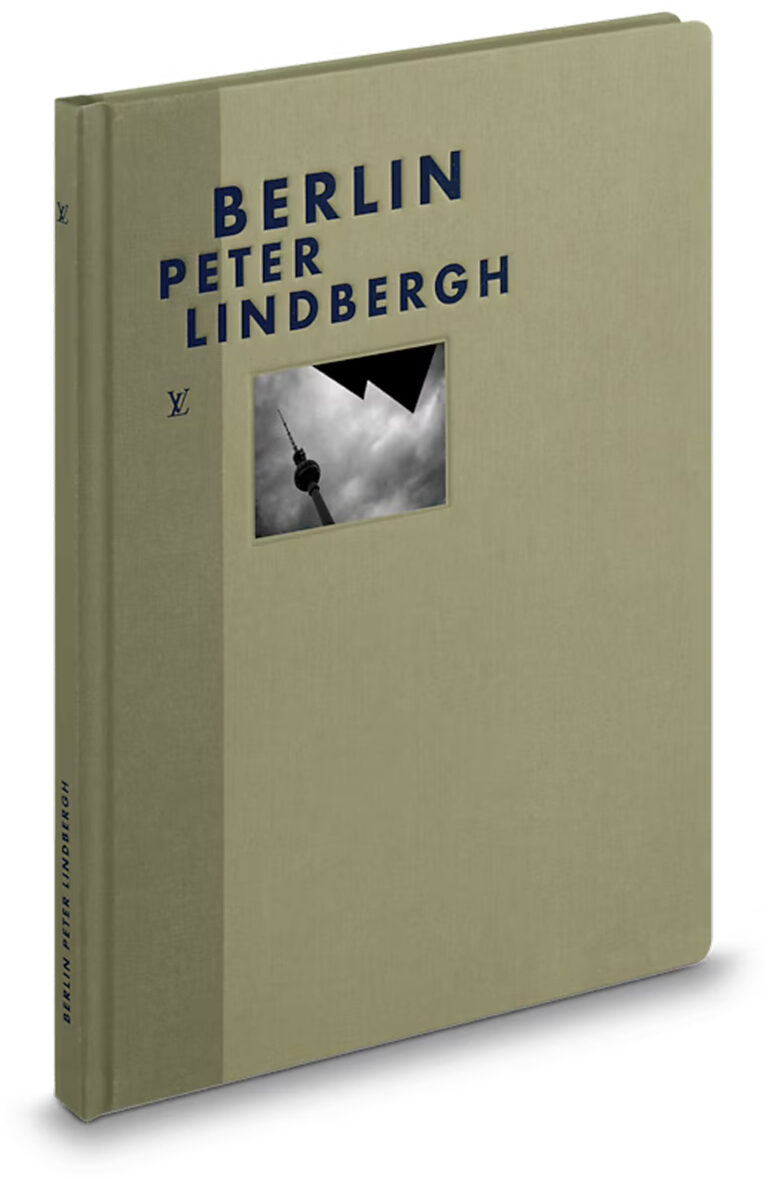

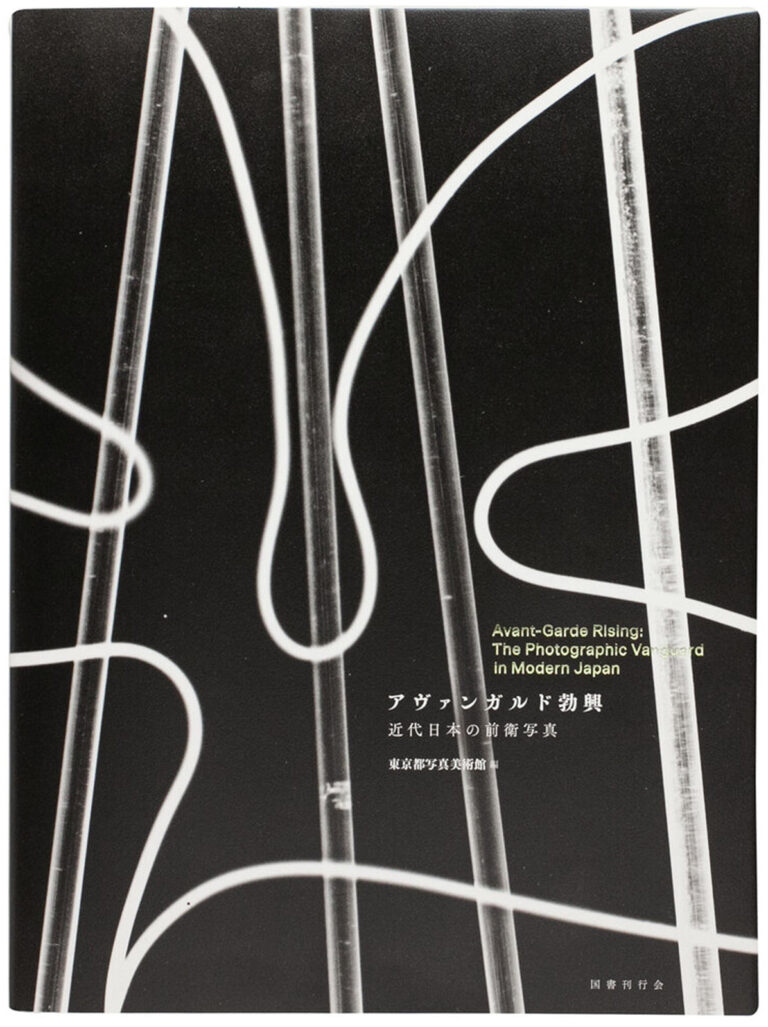

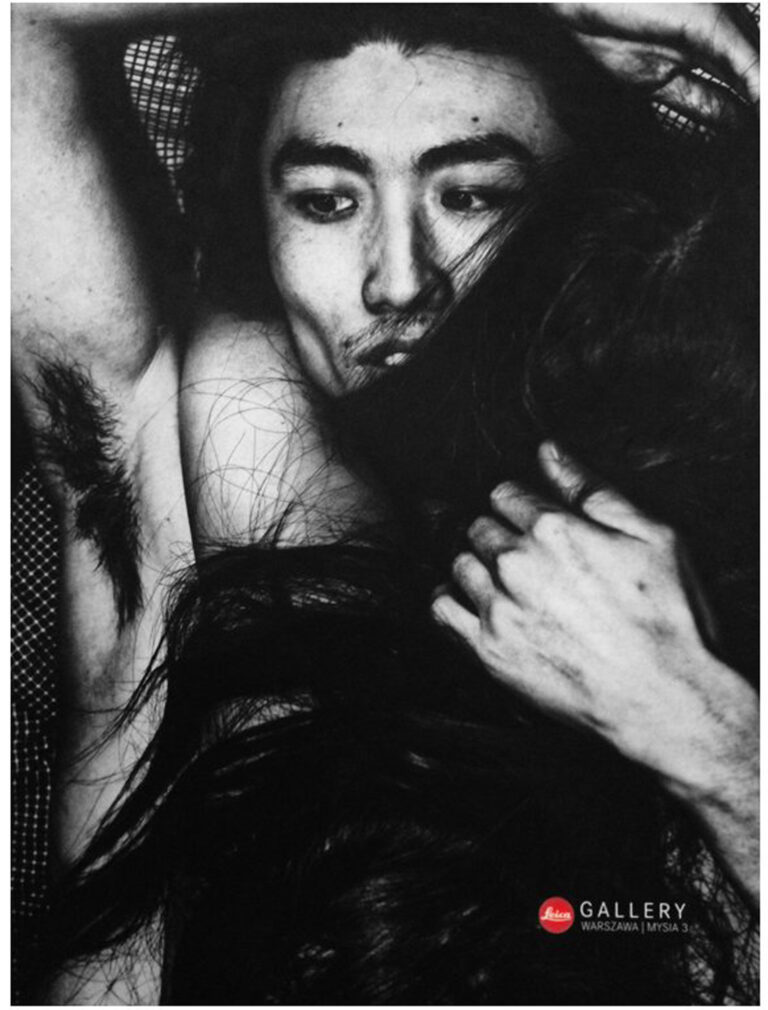

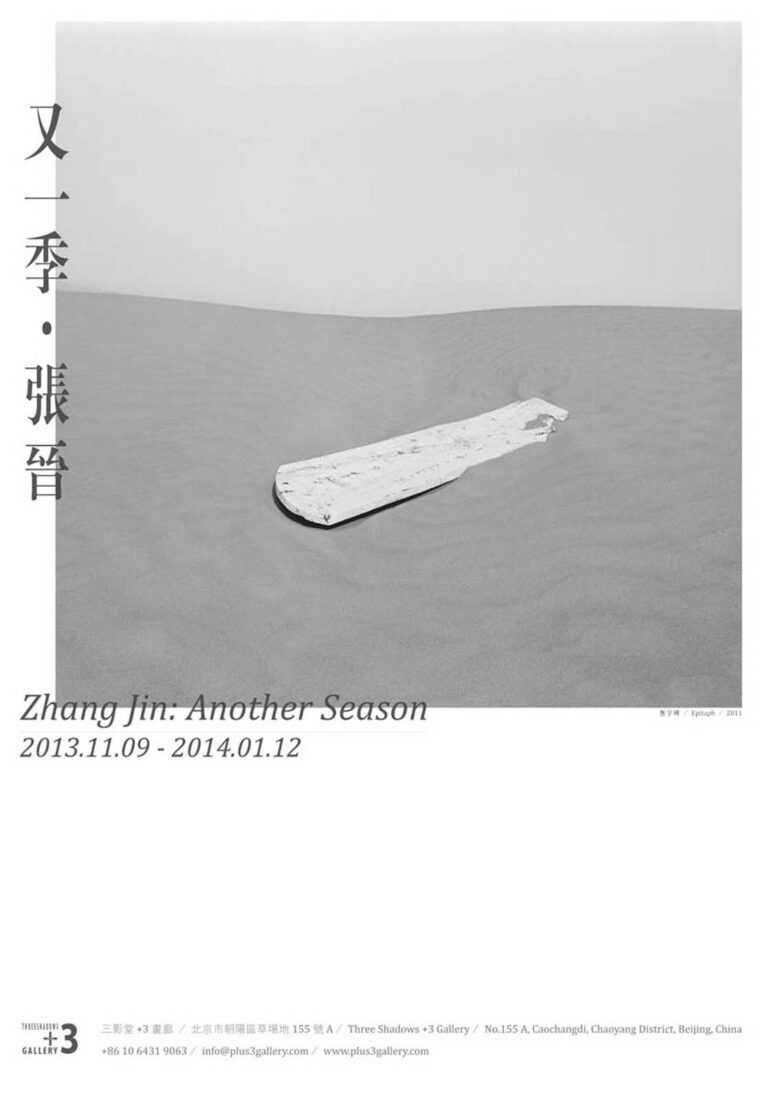

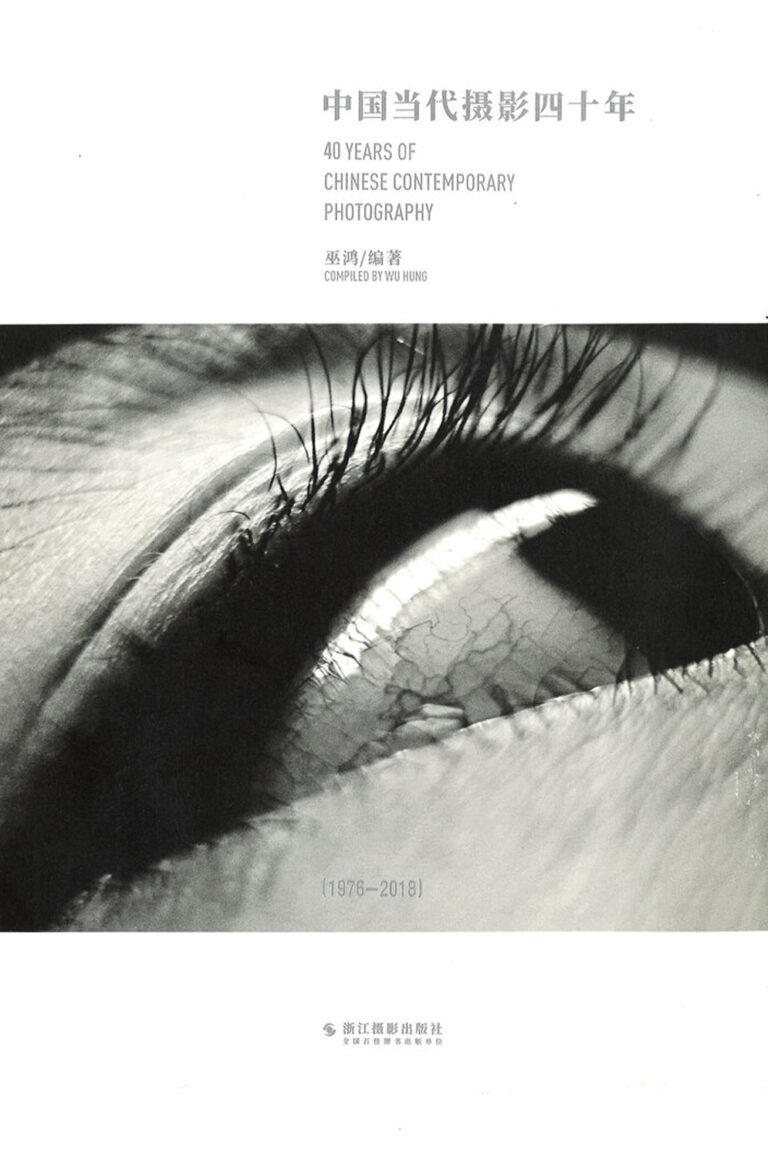

The Ochre Space houses the personal library of João Miguel Barros, a collection of over three thousand photography books. This meticulously curated collection is shaped by diverse thematic lines, with a strong emphasis on post-war Japanese photobooks and works by Chinese photographers who began gaining prominence in the late 1990s.

The library also features works by major names in European and American photography, as well as many emerging authors. It predominantly consists of first editions of books by all these renowned photographers.

Although the library is private, it can be accessed exceptionally by researchers or other individuals who submit a justified request.

This section will make available the titles and authors of all cataloged works. This is an ongoing project, as the collection continues to evolve and grow. The aim is to build a personal, perhaps intimate, narrative of photography through the library’s remarkable holdings.

The Ochre Space Library

ENCYCLOPEDIA

Photography in China

Photography arrived in China in the 1860s with Western photographers, most of whom took portraits.

One of the best known of these photographers was Milton Miller, an American who owned a photography studio in Hong Kong. He took formal portraits of Cantonese merchants, Mandarins and their families in the early 1860s. The other is the Scottish photographer John Thomson (1837-1921), who owned a photographic studio in Hong Kong. Unlike Miller’s subjects, Thomson’s were peasants and workers – the underclass of the late 1860s and early 1870s.

Studios run by Western photographers provided practical training for Chinese photographers and produced some important photographers. Afong Lai and Mee Cheung were active during this period, and both managed to turn their interest to commercial advantage. Afong was active from the 1860s to the 1880s, and in 1937 he published a photo album in Shanghai entitled The Sino-Japanese Hostilities, which presented 110 black-and-white photographs that were seen primarily as historical documents. Some of his landscapes, however, express aesthetic qualities reminiscent of traditional Chinese painting.

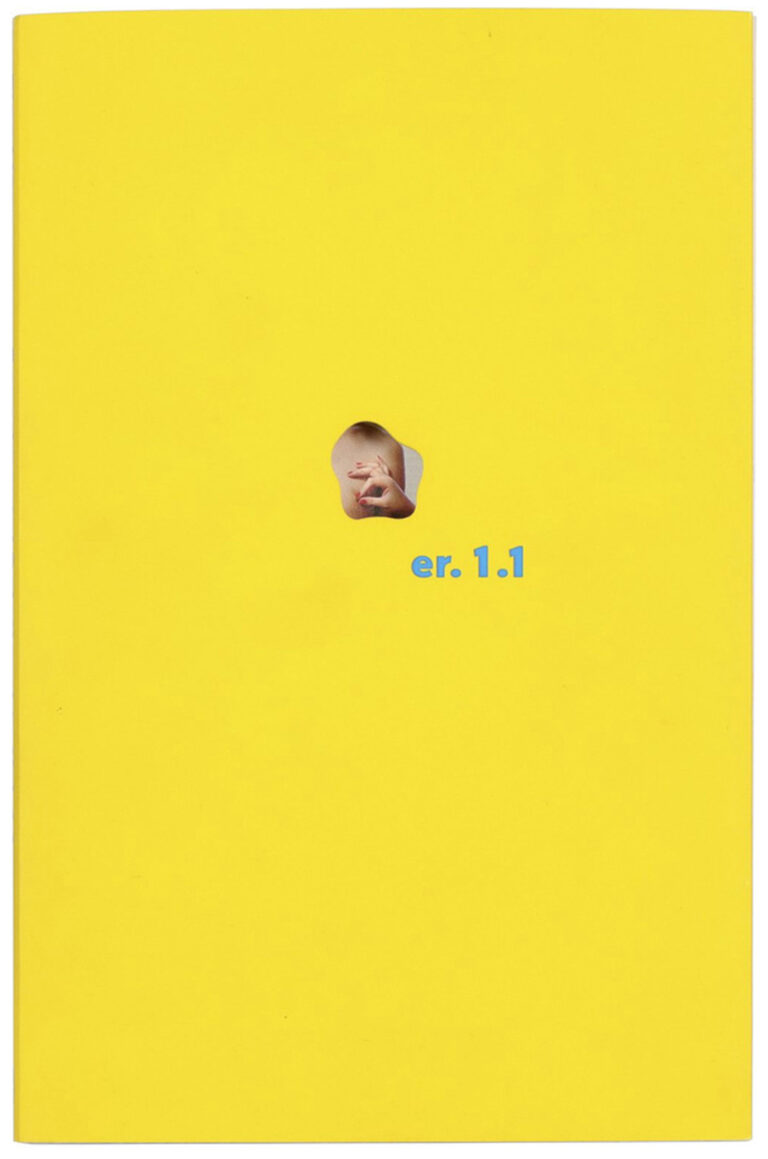

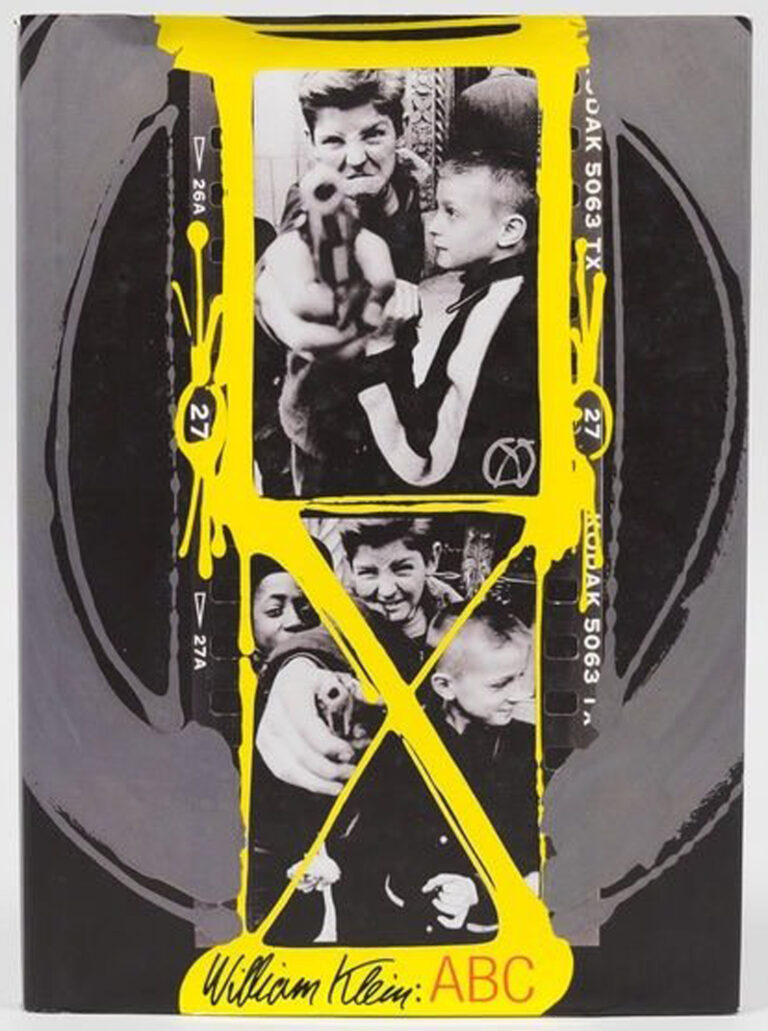

In various forms and contexts, artists’ books have been a dynamic presence in the myriad art movements of the twentieth century. The evolution of artists’ books reflects changes in technology as well as social, political, cultural, and economic developments. Artists’ books have been made from traditional materials and bookbinding techniques, or with radically challenging materials and various methods of composition or presentation that bypass bookbinding altogether. READ+

No single definition of an artist’s book can be both broad and specific enough to be useful, but some book forms can be excluded. For example, some deluxe editions, letterpress work, and handset type do not typify the nature of an artist’s book.

Some artists’ books can be mass-produced using xerography or other economical printing methods.

In the 1950s, Robert Heinecken printed photographs of highly political or pornographic images directly onto the pages of popular magazines, which he then then placed them back on store shelves for sale to an unsuspecting public. Some artists’ books exist in limited editions, perhaps produced in conjunction with a printer, book center, gallery, or museum exhibition or collection. These efforts have proliferated in recent years, but they remain distinct from books called livre d’artist. Some artists’ books may be one-of-a-kind object, but generally the term refers to editioned, mass-distributed materials. Some artists’ books avoid material existence altogether, circulating as performance pieces or as part of the World Wide Web.

Some artists’ books are “containers of information” in which the material support is secondary to the expression or contemplation of personal, political, emotional, or social ideas. In other artists’ books, the object itself is the primary exploration and can exist in many forms. Artist’s books may be bound in traditional accordion folds, various Japanese bindings, or the book may be constructed in a different way that involves no binding at all. The book may consist of pages, be in the form of a scroll, be kinetic and include moving parts, or be sculptural and exist to be viewed as a 3-D work of art. Some artists alter already bound books.

The growth and intensity of work with artists’ books in the twentieth century has several historical references. In 1974, the Grolier Club organized an exhibition and book entitled The Truthful Lens, which described 175 books with original photographs, mostly from the nineteenth century, and claimed that a more complete list might number 2,500 titles. Technological changes in the late nineteenth century, such as lithography, machine-set type, and the linotype machine, facilitated the mass production and distribution of books. This activity did not end the practice of more elaborate bookmaking, and in the early twentieth century the mass production of cheaper editions sometimes included the production of limited numbers of more elaborate copies.

In the 1920s, Russian Constructionism served as a foundation for the idea of books as art. Art movements such as Dadaism, Surrealism, Expressionism, and Futurism sought not only new content but also new forms of expression, and artists’ books were produced by Tristan Tzara, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy.

In the 1930s, Walker Evans established a style often imitated in subsequent photography books, in which the photographs are placed on the right-hand side, and the left-hand side is usually left blank.

Many artists’ books are constructed with this gallery-in-hand presentation.

In the 1950s, the German-born provocateur Dieter Roth shredded paper, then boiled it and stuffed it into animal intestines to make ”literary sausages.” Considered one of the instigators of the contemporary artist book movement, Roth used a variety of found materials, such as commercial printers and rubber stamps to establish many of the conventions of the field. Another seminal figure is the California painter Ed Ruscha. In the 1960s, Ruscha published Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations and made clear his intention to explore book art as primary material, not as a support for his other explorations in art. Ruscha’s books were highly sought after, despite their original modest intention to reach a wider audience in expensive, unlimited editions.

In the 1980s, book art branched out into the performing arts. In a review of the performing arts in the 1990s, British editor Claire MacDonald refers to the theatrical manuscript, describing a new interest in questioning conventional relationships between oral and written texts.

In 1984, the National Endowment for the Arts in the United States added bookmaking to its funding categories. This fund was eliminated a few years later.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, a number of new printmaking facilities were established in Great Britain, Europe, Japan, and the United States, combining craft techniques in papermaking and bookbinding. These facilities are sometimes part of a university or art school, sometimes a private institution such as New York City’s Center for Book Arts or the Purgatory Pie Press. Book arts centers can provide facilities for making work, as well as funding and an infrastructure for exhibiting the results. In 1965, Stan Bevington founded Coach House Press in Toronto, primarily to publish Canadian authors, but also to produce more artisanal books. Since 1972, the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, under the direction of Joan Lyons, has produced more than 200 books, including artists’ books as well as critical or historical titles on the visual arts. Other book arts centers include the Pacific Center for the Book Arts (California), Printed Matter Bookstore and Franklin Furnace (New York City), Bookworks (London), Art Metropole (Toronto), and the Women’s Study Workshop (Rosendale, New York).

Founded in 1976, Franklin Furnace has taken an active and often controversial role in the production and distribution of artistic work not supported by existing arts organizations. In 1979, Franklin Furnace exhibited work curated by several prominent art world figures, including Clive Phillpot, whose curatorial, writing, and other activities made a significant contribution to the book arts in the twentieth century. Nexus Press (Atlanta) is run by and for photographers who want to publish their own books. In 1976, Chicago Books appeared, inviting six to ten artists a year to produce a book in its facilities. In 1977, the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland, expanded its activities to include the production of artists’ books. Pyramid Atlantic, a book arts center in Maryland, opened in 1981 under the direction of Helen Fredrick.

Thus the expansion of funds and facilities for the production of artists’ books progressed, but the diffusion of such objects remained problematic throughout the century. Their uniqueness often makes them both valuable and inaccessible. Sometimes artists’ books can be displayed in traditional venues for books, such as bookstores, coffeehouses, reading rooms, or libraries. Sometimes such objects are best distributed through more traditional art venues such as galleries, museums, and art fairs.

Art fairs dedicated to books provide a fertile for artists and collectors to compare otherwise singular, isolated works. Pyramid Atlantic hosted half a dozen such book fairs in Washington, DC, in the 1990s. In New York City, the Brooke Alexander Gallery presented artists’ books in conjunction with the annual Armory Show of prints and drawings. By the end of the century many individuals, universities, and museums began collecting and exhibiting artists’ books, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Manchester Metropolitan University, and the Carnegie Mellon Libraries, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Fears that the mechanical and digital technological changes of the twentieth century would spell the end of the artist’s book did not materialize and the book as object remained a leading genre in the art world. Technological advances made desktop publishing an increasingly democratic possibility, complementing works in expensive materials with works available for low-budget projects. By the end of the century, immaterial books existed on computer screens via the World Wide Web.