Photography in Taiwan

Photography was probably introduced to Taiwan as early as 1871, when the Scottish photographer John Thomson (1837-1921) visited the island, then called Formosa, during his travels in China from 1868 to 1872. Thomson is best known for his ambitious album of portraits of Chinese workers and peasants, published in England in 1893/4 as Illustrations of China and Its People. He appears to have been the first photographer to make landscape photographs and portraits of aboriginal people in Taiwan.

Other photographers during this period were Christian priests who lived and worked in Taiwan. They often took portraits of the native people

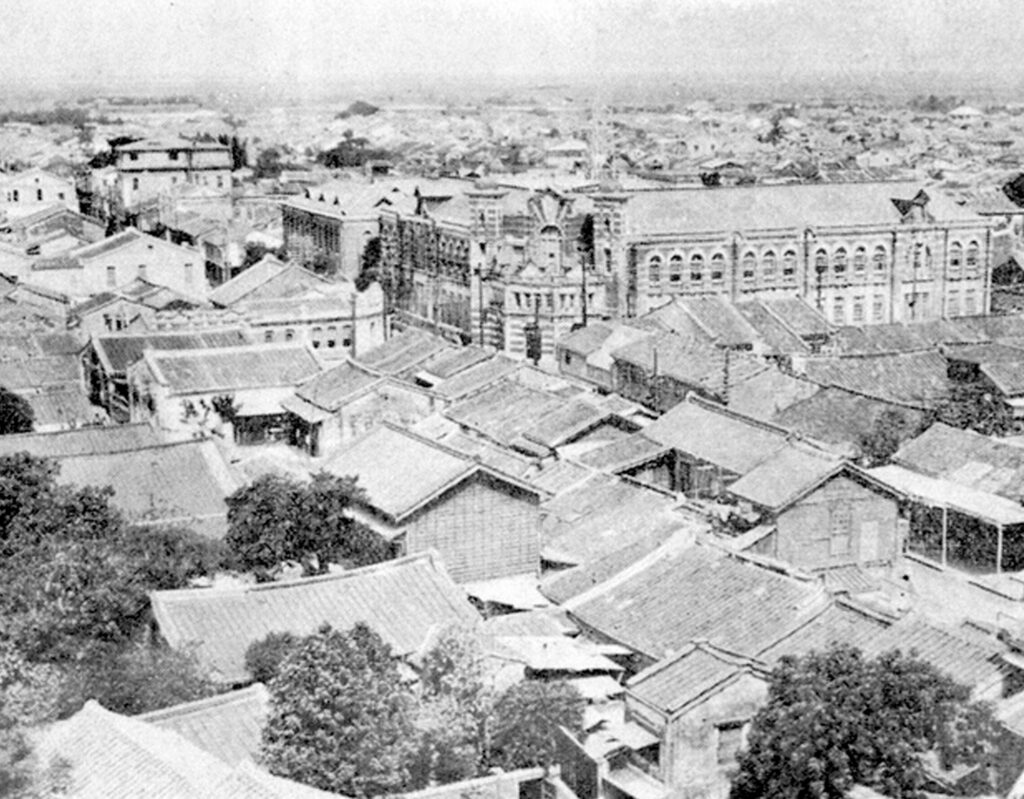

Photography in Taiwan, from 1895 to 1948, during Taiwan’s Colonial Period under Japanese Occupation, was heavily influenced by the Japanese. Documentary photography was widespread, although it was mainly used by Japanese anthropologists, scholars, and reporters during the early period of the Japanese occupation (1895-1920), as cameras were mostly considered research tools for field work in the newly acquired colony. Portrait photography was the other popular type of photography. As a colonized island under the Japanese, Taiwan was severely restricted. Native Taiwanese could not afford to purchase the cameras and photographic equipment that Japanese and some British companies had. Even so, Taiwanese were not allowed to purchase negatives or experiment with chemicals or other photographic materials.

The difficult conditions, however, did not completely prevent the use of photography. Japanese photographers and reporters based in Taiwan ran the photo studios and shops, but also offered some photography classes to introduce the local population to the functions of cameras and basic darkroom techniques. This was done for commercial reasons to meet the demand for portrait and documentary photography, and there was no formal or professional photography education in the schools. Thus, the master-disciple system was heavily used in the commercial photography studios. SHR Chiang and LIN Tsao were two important figures who emerged in the midst of these conditions. They were trained in the master-disciple system and later established their own commercial studios. In 1901, Shr Chiang founded the first Taiwanese owned and operated studio called Duplicated Me Photo Shop, which existed until 1946. Around the same time, Lin Tsao (1881-1953) inherited a studio from his teacher Mirimoto, a Japanese reporter living in Taiwan. He renamed it Lin Photo Shop.

Shr Chiang, Lin Tsao and others who set up shops were largely patronized by Japanese officials to record their activities and report on propaganda events.

PENG Ruei-lin stands out as an exceptional photographer of this period. Like his predecessors, he ran a photo shop to support himself. Unlike them, he had received formal training in photography at a professional school in Tokyo, in the 1920s. This training made a significant difference in his approach to the medium. He experimented with various techniques of color photography,, in 1930 and infrared photography, in 1933. While both areas had been discovered and discussed by Western photographers, they were little known in Taiwan. Peng Ruei-lin’s experiments illustrate how, even in artistic isolation, he was able to use the camera for artistic creation and attempt to achieve aesthetic effects. However, Peng Ruei-lin’s significance was not widely recognized by other local photographers, and his concerns did not enter the mainstream understanding of photography in Taiwan. From 1933 to 1937, he taught classes continuously in his photo shop, and many of his students became key figures in photography after the Japanese left the island.

TENG Nan-kuang (b. 1907), CHANG Tsai (b. 1916) and LEE Ming-diao (b. 1922) were the most active and influential photographers during the late colonial period and the Sino-Japanese War from 1934 to 1948. They have been called the “Three Swordsmen of Taiwanese Photography” to identify their roles as strong promoters of photography in Taiwan, especially during the 1950s. Stylistically, their photographs are reminiscent of Japanese realism in documentary photography, where the dominance of the realist style leaves little room for photographers’ individual creations. However, unlike the early documentary photography of Taiwan so influenced by the Japanese style, the works of these three figures create a more humanistic sense and express each photographer’s concern and individual awareness of Taiwan. Traveling throughout Taiwan, Teng Nankuang, Chang Tsai, and Lee Ming-diao captured images that showed their interest in early Taiwan’s rural culture, religious rituals, and social conditions. Teng’s most famous work is a series of so-called tea ladies. He took candid portraits of the ladies at work. Chang traveled to Orchid Island, an isolated island off Taiwan, and painstakingly photographed aboriginal people in great detail near Jade Mountain, Taiwan’s highest elevation, capturing his subjects in a straightforward and direct way. Lee is known for his photographs of rural life and traditions rooted in Han Chinese culture. Though trained as documentary photographers or photojournalists, the Three Swordsmen were not primarily motivated by commercial or political agendas like their early Taiwanese counterparts, and their work was instrumental in encouraging local photographers to reevaluate the aesthetic potential of the medium.

The Three Swordsmen also helped shape the environment of photography in Taiwan. Teng established networks and a photographic association, and promoted formal education in photography in schools. In 1953, together with LONG Chin-san, he co-founded the Chinese Photography Association, the first association for professional photographers.

This association helped to gather photographers, exchange knowledge, and promote public understanding of the aesthetic dimension of photography. In 1964, Teng founded the Taiwan Photographic Society with the dual aim of rejecting the motifs of salon photography and promoting modern photography in Taiwan. Chang initiated photography classes in professional training schools. Lee published the first professional photography magazine in Taiwan, which was distributed through photography stores. The magazine published the texts of updated theories and concepts of photography.

LONG Chin-san (b. 1892) was a leading photographer and an influential promoter of photography in mainland China and Taiwan, having moved to Taiwan from mainland China after World War II. Long is considered one of the earliest pioneers of photography in the early 1900s and one of the most active photographers in mainland China. His photographic experiences in China made his work conceptually and stylistically different from that of other Taiwanese photographers.

Unlike photographers trained in Japan and Taiwan, Long’s approach to photography pays attention to both the technical and aesthetic dimensions of photography. His early training in Chinese ink painting contributed to his understanding and skill with the artistic elements of photography.

In 1961, Long adopted a unique photographic practice known as montage pictorial photography. Montage pictorial photography was groundbreaking in the history of photography because it used photographic techniques to express the aesthetics of Chinese ink painting. The basic concept of montage pictorial photography is to create a black and white photograph based on the classical theory of Chinese ink painting, commonly known as “the six principles of painting”. For Long, photography was capable of presenting the beauty and aesthetics of traditional Chinese art and culture, with two factors determining whether a photograph could be considered art – artistic composition and a significant message embedded in the work. For Long, posing a scene in a traditional Chinese painting is not unlike composition in photography, although in painting an artist can adjust the positions of the compositional elements, whereas a photographer is limited by the mechanical eye.

Through photographic techniques, a photographer can solve this problem. The process of making a photograph that can be characterized as a montage photograph is complex – it involves planning the subject, taking the pictures, planning the layout of the pictures, collaging the negatives through darkroom techniques, including darkroom techniques and including multiple exposures. Although Western photographers since the 1920s have used darkroom techniques that achieve image overlap similar to Long’s concept of composition, Long’s montage pictorial photography depends on the unique considerations of Chinese painting principles.

The Scenery of Lake and Mountain is now generally regarded as Long’s most typical ”compositional” image. A landscape composed of shots of an old man sitting in a pavilion amidst rocks and pine trees, a boat, villages, and a lake, the composition depicts a narrative typical of a traditional Chinese landscape. The space created in the photograph abandons the principle of three-point perspective, and the gradated tonal effects in the photograph are also reminiscent of a Chinese ink painting.

In contrast to the salon style and pictorial photography advocated by Long Chin-san, a number of styles have emerged that are characterized by what is known as intentional photography and other modern styles.

KE Shi-jie (b. 1929) is one of the most important photographers to work with intentional photography. In his early work, he shot a series of portraits and landscapes, and was concerned with the personal characteristics and aesthetic quality of his subjects. He later moved to New York and became a commercial photographer. After leaving his job, he spent several years in the late 1970s and early 1980s traveling the world and taking photographs.

The resulting works are abstract, with dreamlike landscapes that appear to be influenced by Surrealism, emphasizing the tonality of shadows.

His most famous works include Living Tao, Still Vision, Dancing Brushes, Embrace Tiger, and Return to the Mountain. Other intentionalist photographers include HSIEH Chun-teh (b. 1949) and Denial LEE. They emphasize the photographer’s interpretation of his or her subject, rather than simply reporting or documenting it, and are concerned with the elements of color, form, composition, and contrast in their work.

The modern photography movement in Taiwan began around 1965 and lasted for about ten years. It is important to note the American influence on Taiwanese photography during this period. After World War II, the U.S. Army established bases on the island. Taiwan shed Japanese influence and absorbed American culture and art, motivating photographers and shaping the development of photography. Key figures in this development include JANG Jao-tang, HU Yung, Hsieh Chun-de, among others, who used wide-angle lenses to create distorted images, favoring high contrast between light and dark, rough grain, and blurred or out-of-focus images. This tendency did not permeate the entire field of photography in Taiwan, but was limited to a group of photographers who held joint exhibitions. One such exhibition was held in 1969 and featured the work of eight photographers who were active in this movement. Ambitious photographers made a number of attempts to raise awareness of modern trends in photography. In 1966, a photo festival was dedicated to modern photography.

Two important magazines were published: Photo Century in 1970 and Modern Photography in 1976.

Riding the wave of this cultural shift was V-10, a photography group founded in 1971. It aimed to promote discussion among modern art, photography and visual media. Among the founding members were JOU Dung-guo, Hu Yung, NING Mingshen, GUO Ying-shen, JANG Guo-shiung, JANG Jao-tang, JUNG Ling, YE Jeng-liang, LUNG Szliang, SHIE Jen-ji; and in 1973 the group expanded to include HUANG Yung-sung, SHIE Chuen-de, JANG Tan-li, LIU Chen-tzuo, LI Chihua, WU Wen-tao. None of them continued to work as full-time independent photographers, but instead worked for newspapers, TV stations, advertising agencies, and filmmakers. Some of the founding members had participated in experimental theater and film. Their photographs were often published in Photo Century, an important magazine of modern photography in Taiwan. Although these photographers did not share a unified aesthetic principle, they participated in several group exhibitions in the 1970s.

Despite the efforts of some photographers, photography in Taiwan in the mid-1970s and 1980s was dominated by photojournalism. The development of this style is linked to several political events of the time, a tumultuous period in political and international relations. In 1971, Taiwan was expelled from the United Nations, and in the same year, the Japanese government took possession of a small island claimed by both Taiwan and mainland China. Taiwan’s sovereignty, threatened by absorption into China, became a critical issue that provoked the consciousness of photographers and artists, who sought to identify and preserve Taiwan’s culture, society, and people.

Photography in Taiwan during these 20 years thus developed into a style of social realism that was prevalent in photography magazines, popular magazines, and newspapers.

It is important to note that several photographers had begun to work in a reportage style in the 1960s, notably JANG Shr-shian, CHENG Shang-his, and HSU Ching-po.

Cheng Shang-his was a leading reportage photographer who worked for three major magazines. After its publication, his Story of the HungYe Baseball Team was considered one of the early examples of reportage photography in Taiwan.

Another of his well-known works is The Series of Jilung (1960-1965), which documents the changes in his hometown. Inspired by his teacher Chang Tsai, he used a snapshot style with simple and straightforward compositions to capture his subjects. His student, JANG Jao-tung, later became a very active and important reportage photographer, and in 1965 the two of them held an exhibition dedicated to modern photography.

The emergence of several photography magazines and newspapers was essential to the advocacy and popularization of the style, and allowed serious photojournalists to emerge, including WANG Xhin, LIANG Jeng-jiu, and LIU Chen-hsiang.

Echo magazine was first published in 1971 with the aim of introducing Chinese culture and promoting cultural exchange between the West and the East. In 1978, the magazine abandoned its English version and launched a Chinese version with a special issue on Chinese photography. It encouraged interest in reportage photographs of Taiwanese culture and featured exclusively their works, including those of HUANG Yung-sung and JUNG I-jong. These reportage photographers aimed to discover the neglected aspects of life in Taiwan, and they played a pioneering role in this widespread cultural phenomenon, which also attracted the contributions of novelists and other artists. These photographers were also involved in organizational and editorial work.

In 1973, GAO Shin-jiang, editor of the Arts and Literature section of The Times in Taiwan, devoted several columns to photojournalism.

This was the first newspaper in Taiwan to strongly support photojournalists and present their various documentaries on Taiwanese culture and Taiwanese minorities.

In 1985, novelist CHENG Yin-jen published a magazine called Renjian-literally – “the world in which people live”- specializing in text and images for an intellectual Taiwanese audience. This magazine sought to characterize reportage photography as humanistic and truthful, dedicated to providing critical insight into what had become an overwhelmingly materialistic culture and consumer society. The magazine did not focus exclusively on Taiwan, but also covered the critical problem of hunger in Ethiopia. Although the magazine only ran for four issues, ending in 1989, it served, along with other publications, to foster the emergence and development of reportage photography in the 1980s.

The cover of the first issue of Renjian was GUAN Xiao-Rong’s ”Bachrmen” from his series on the aboriginal people of Orchid Island. Guan Xiao-Rong photographed exclusively on this island for almost 10 years, moving there to live, and his work tends toward ethnographic documentary.

He later helped found an Aboriginal foundation and was even personally involved in Aboriginal protests in the 1990s. In ”Bachrmen,” he documented a community of Aborigines who had moved there illegally, attracted by the low cost of living.

JUNG I-jong, another active photojournalist, was trained in woodblock printmaking; an active editor and writer, he had no professional training in photography. Man and Land (1974-1986) was his first reportage work, inspired by his memories of his youth and its impact on his adult life. Taipei Tumor focuses on the city of Taipei, depicting its rapid and chaotic development.

Szu Chin (1980-1985) documents Taipei’s rural aboriginal reservation community. Motivated by his experiences growing up near the area and his encounter with a mysterious saying about the community, and influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s concept of the ”decisive moment,” Jung employs a snapshot style in this series. In 1992, he founded Photographers, which introduced international photography to Taiwan and vice versa. The magazine has been an important source for aspiring photographers to understand the work of the masters. He has also published numerous books on photography, which have benefited people in both Taiwan and mainland China.

Female photographers are less common in Taiwan than in mainland China, and WANG Shin is the first female photographer to focus primarily on reportage. She studied photography in Japan and worked on a series of photographs about a violent incident in an aboriginal community during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan.

Taiwan has also experienced an exodus, as some photographers have left the island to study and work in America.

Daniel Lee (b. 1945) moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1970 to study photography and film after training as an oil painter in college. He then spent a decade working in a commercial studio in New York. In the early 1990s, he entered the field of digital photography. Today, he is hailed as one of the world’s pioneering photographers, and his early works have inspired many Taiwanese to experiment with digital photography.

Motivated by the emergence of new technologies in everyday life, Lee sees the use of digital imaging tools as a way to have more freedom in selecting subjects, expressing his concept, and controlling the outcome.

He created his first digital series in 1993. Entitled Manimals – a word that combines the words man and animal – in this series of 12 compelling yet disturbing images, Lee accentuates various human features to evoke those of an animal to create the 12 animal signs of the ancient Chinese zodiac associated with birth years, such as ”1949-Year of the Ox’.’ The concepts of Lee’s works are related to Buddhism and Taoism, and the cycles of life and reincarnation of the religious beliefs he encountered during his life in Taiwan. He is also interested in Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Other works include 108 Windows (1996-2003), Origin (1999-2001), and Judgement (2002). Origin refers to the origin of man as proposed by Charles Darwin. The concept of Judgement is taken from Taoist folklore about the underworld. In this myth, each individual is presented to the judge of the court in the underworld after death. This work is associated with the cycle of life and reincarnation.

As in the People’s Republic of China, digital photography and video are popular contemporary art forms in Taiwan.

CHEN Chieh-jen (b. 1960) is interested in violent events in modern Chinese history and presents his interpretations of the Japanese invasion of China in the 1930s. Using digital techniques to mimic historical photographs depicting horrific acts, including beheadings, Chen Chieh-jen explores issues of the body, national identity, and political power. His works are also inspired by notions of Chinese Taoism in their depiction of the life cycle and the afterlife.

HUNG Tung-lu (b. 1968) is interested in cyber culture and the figures that represent it in Taiwan and Japan, creating figures based entirely on his imagination using digital techniques that address the question of what human beings might become in the advancing cyber culture. He has explored answers to this question in Buddhist teachings and incorporates the idea of Nirvana into his cyber creations, which are holographic in nature and mounted in light boxes.

WU Tien-chang (b. 1956) uses digital photography to mimic posters that might be found in Shanghai, incorporating aspects of ancient Chinese myth, folklore, and Taoism into the narrative of his works.

CHEN Shun-chu (b. 1963) explores the concept of family. He has been taking portraits of his family members and others since 1992 and has accumulated hundreds of photographs. In his works, he explores social relationships and their connection to the concept of family, and extends this concept to the idea of home.

YAO Jui-chung (b. 1969), a pioneer of contemporary Taiwanese photography, remains a leading photographer. He is also very active as a curator and is known for his critical writings on contemporary art and photography in Taiwan. In an early series of photographs, he created upside-down self-portraits as a parody of Taiwan’s national identity in relation to China. He is also interested in ruined or abandoned landscapes in Taiwan and the issues of cultural identity that these landscapes raise.